Some afterthoughts on “Bare-handed”

by John Rockwell

One of the first things I did as the newly ensconced chief dance critic of The New York Times in January 2005 was immerse myself in the Dance on Camera Festival at Lincoln Center. The first thing I did in my newly retired state from The New York Times was attend the Dance on Camera Festival in January 2007.

I am writing now about one of the films I saw early this year, Thierry Knauff’s “Bare Handed.” To my knowledge, the jury did not even pick this is a finalist, let alone give it the jury award. In 2005 my taste and that of the jury (and of nearly everyone else who saw it) coincided: Lloyd Newson’s “The Cost of Living” was clearly the best entry that year, and walked away with the prize. So, I brooded, if my taste corresponded with that of the jury then, why not now?

Knauff is a Belgian with an interesting background as a filmmaker. He was born in Kinshasha in the (formerly Belgian) Congo, and has made several documentaries about Africa, including “Baka” (1995) on the Pygmies of southeast Cameroon. He also has an intense interest in dance and music, the latter seen in his poetic docu-biography of the composer Anton Webern, in which scenes from his life are evoked wordlessly (wonderful if you know the story, mystifying, I would suspect, if you don’t). That film seems to have inspired his first feature, “Wild Blue” (2000), described as a floating tonepoem collage of sounds and images.

Subsequently, in this millennium, Knauff has collaborated on two films with the dancer-choreographer Michele Noiret. She studied at Bejart’s Mudra school in Brussels and was closely associated for a time with the composer Karlheinz Stockhausen. She is also the daughter of Joseph Noiret, a leading Belgian “revolutionary Surrealist” and founder of COBRA, an artistic collective devoted to advancing the cause of, it seems, revolutionary Surrealism.The first Knauff-Noiret film (2004) was called “Solo”, and in information distributed by Knauff’s Films du Sablier it is the first half of a “two-part variation” that also includes “Bare Handed” (2006). Despite some intriguing music by Stockhausen, “Solo” is the less interesting of the two, although pretty striking on its own terms. It is also more overtly dancey, in that it follows Noiret in a scary dreamscape but concentrates on her angular, gestural dancing.

Both films last about 30 minutes and are in black and white with stark side lighting. But “Bare Handed” is considerably more ambitious filmically and theatrically. Again, Noiret stalks and writhes about in black. But this time there are ever-present, sometimes large-than-life projections on a screen behind her and, more touchingly, an old man with quivering hands and elegant, shaky handwriting who periodically appears from behind the screen, watching silently. His words and her whispering into his ear circle back, over and over, to dreams. The old man turns out – when you read the credits – to be Joseph Noiret.

I found “Bare Handed” – the French title, “A Mains Nues,” means exactly the same thing but is somehow more sexy and mysterious – compelling from start to finish. Without knowing the tastes of the 2007 jury, I can only speculate that Knauff’s entry failed to make the cut for the jury prize because it seemed more theatrical and filmic and less choreographic – more a Knauff film than a Noiret film.

Of course this is a false dichotomy, especially in the closely-linked intersections of dance, theater and film in Europe today. But American dance critics seem still more closely wedded to “pure” dance abstraction in the Balanchine-Cunningham mode. The very notion of dance on camera suggests a marriage of those two art forms. But maybe there is still a bias here towards film as a handmaiden of dance, better serving the purposes of documentation and celebration than incorporating movement into film for more overtly cinematic purposes.

Then again, “The Cost of Living,” for all its choreographic brilliance, was plenty theatrical. So maybe this time around my taste simply differed from the Dance on Camera jury. “Bare Handed” is still worth seeking out. It’s a powerful work, whatever its genre may be.

John Rockwell will be a member of the Dance on Camera Festival 2008 Jury, along with Alla Kovgan, David Michalek, Gerald Busby, and Lana Wilson.

SPARTACUS opens Dance on Camera Festival 2008

Both films last about 30 minutes and are in black and white with stark side lighting. But “Bare Handed” is considerably more ambitious filmically and theatrically. Again, Noiret stalks and writhes about in black. But this time there are ever-present, sometimes large-than-life projections on a screen behind her and, more touchingly, an old man with quivering hands and elegant, shaky handwriting who periodically appears from behind the screen, watching silently. His words and her whispering into his ear circle back, over and over, to dreams. The old man turns out – when you read the credits – to be Joseph Noiret.

I found “Bare Handed” – the French title, “A Mains Nues,” means exactly the same thing but is somehow more sexy and mysterious – compelling from start to finish. Without knowing the tastes of the 2007 jury, I can only speculate that Knauff’s entry failed to make the cut for the jury prize because it seemed more theatrical and filmic and less choreographic – more a Knauff film than a Noiret film.

Of course this is a false dichotomy, especially in the closely-linked intersections of dance, theater and film in Europe today. But American dance critics seem still more closely wedded to “pure” dance abstraction in the Balanchine-Cunningham mode. The very notion of dance on camera suggests a marriage of those two art forms. But maybe there is still a bias here towards film as a handmaiden of dance, better serving the purposes of documentation and celebration than incorporating movement into film for more overtly cinematic purposes.

Then again, “The Cost of Living,” for all its choreographic brilliance, was plenty theatrical. So maybe this time around my taste simply differed from the Dance on Camera jury. “Bare Handed” is still worth seeking out. It’s a powerful work, whatever its genre may be.

John Rockwell will be a member of the Dance on Camera Festival 2008 Jury, along with Alla Kovgan, David Michalek, Gerald Busby, and Lana Wilson.

SPARTACUS opens Dance on Camera Festival 2008

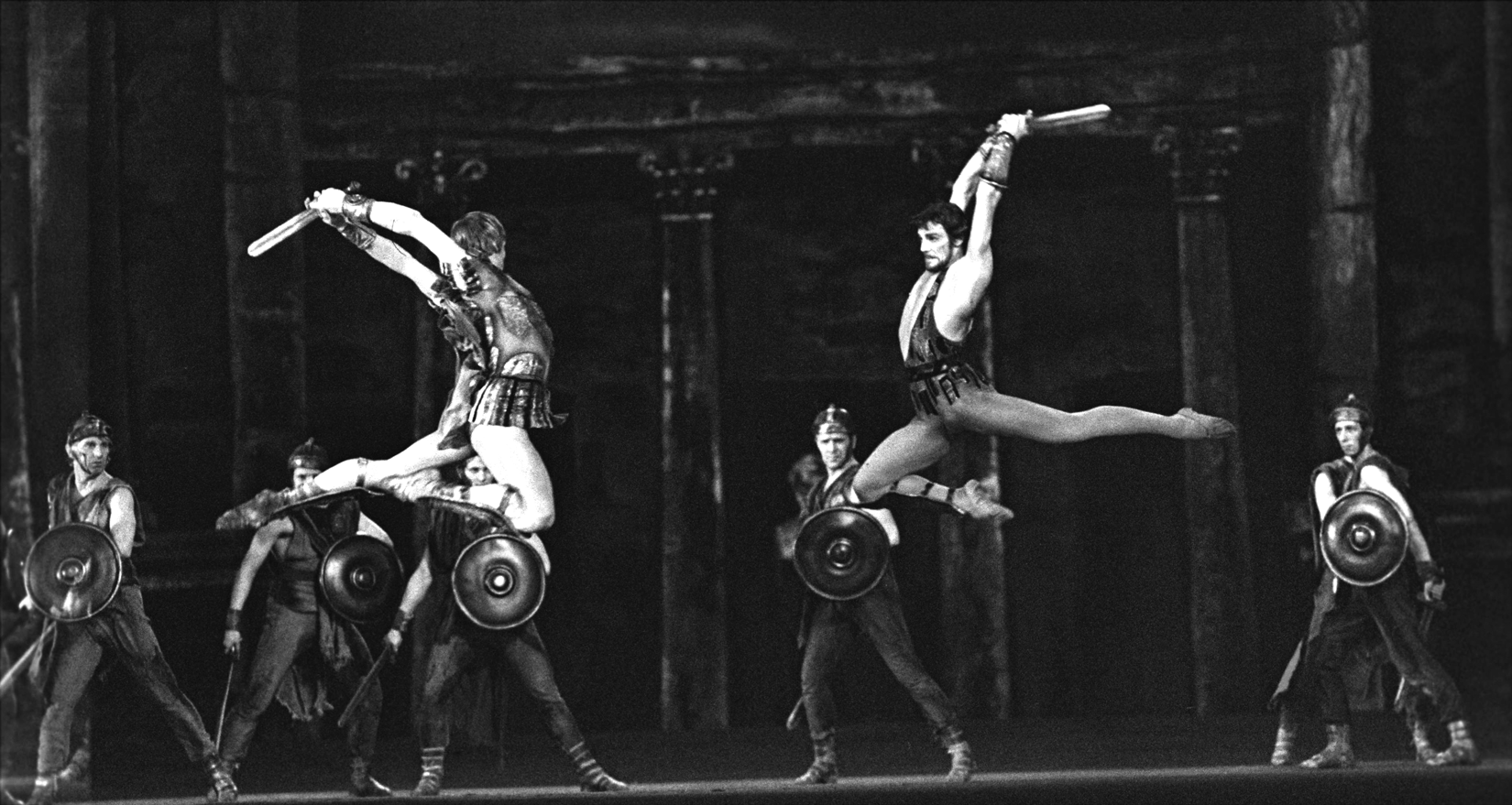

SPARTACUS, the recently restored 1975 ballet film based on Yuri Grigorovich’s staging for the Bolshoi Ballet, will have its world premiere at the Walter Reade Theater as the opening film for DFA’s 36th annual Dance on Camera Festival 2008 co-sponsored by the Film Society of Lincoln Center. It stars the incomparable Vladimir Vasilyev, Natalya Bessmertnova, Maris Liepa as the villainous Crassus and Nina Timofeeva as the vampish Aegina, each dancer a renowned star of the famed Bolshoi Ballet at the time. This ballet-drama is a Soviet-Era vision of the much depicted uprising by Roman slaves, a grand cinematic spectacle, loaded with drama, romance and heroics to a score by Aram Khachaturian.

The epic Spartacus also inaugurates the upcoming series “Envisioning Russia : A Century of Filmmaking” (January 25 – February 12, 2008) which includes films from virtually every decade of Russian cinema and demonstrates its undeniable power and importance in the world. Co-presented with Seagull Films, the line-up of highlights includes films by notable directors such as Konchalovsky, Tarkovsky, Shepitko and Panfilov, as well as some earlier examples from the 20’s and 30’s, including a hilarious musical, “Vesoloye Rybata” (“Jolly Fellows”) that shows that Hollywood did not have a monopoly on this beloved genre.

Thinking of gladiator movies, we googled for some information and came across a very entertaining writer Richard von Busack who allowed us to reprint some of his work below.

“Roman Charges. The revival of the gladiator epic says as much about American politics as it does about ancient history.”

“In youth, the idea that there was once an age of heroes with swords and shields is picked up second-hand, like gossip. As always, that peerless source of forbidden information, the movies, filled in the details. As a kid, I was unable to tell the difference between movies and news broadcasts anymore than I could tell the difference between a painting and a photograph. How was I to know that gladiator movies weren’t newsreels?”

“Cinematically speaking, gladiators have been pushing up the gladioluses for four decades–the roots of both words are the same, no surprise to anyone who’s seen the “little sword” of a gladiolus shoot piercing the ground. These films were once inescapable, on “Gladiator Wednesdays” on KTVU or at “50-cent matinees’.”

“Most of these 150 or so films fit Charlton Heston’s definition of gladiator spectacles: “The easiest kind of movie to make badly.” As with science fiction movies, the good ones were great and the bad ones were better. Still, these gladiator films often proved to be more historically accurate than the Westerns and costume dramas of the time.”

“Jon Solomon, a classics professor from Columbia University who wrote the best book on the subject, The Ancient World in the Cinema (Barnes, 1978), praises the way the films summed up “the power, complexity and excitement of ancient life … respecting a money-paying audience as well as the heritage of mankind.”

“Gladiators count as one of the good parts of history, the part that can wake up a sleepy classroom. The gladiator picture provides the average American’s only exposure to the ancient world. At best, the gladiator movie presents a quick idea of how the Roman Empire looked and worked–and didn’t work.”

“Broad-sword conflict is always good for thrills, but the movie-going experience is deepened by the memory of one of the most famous of Roman tags: the poet Horace’s “Mutato nomie de te fabula narratur“–“change the names, and that story is about YOU!”

To read the full article of Richard von Busack on-line, visit www.metroactive.com/papers/metro/05.04.00/cover/gladiator1-0018.html

FLAMENCO AT 5:15

notes by director Cynthia Scott

SPARTACUS, the recently restored 1975 ballet film based on Yuri Grigorovich’s staging for the Bolshoi Ballet, will have its world premiere at the Walter Reade Theater as the opening film for DFA’s 36th annual Dance on Camera Festival 2008 co-sponsored by the Film Society of Lincoln Center. It stars the incomparable Vladimir Vasilyev, Natalya Bessmertnova, Maris Liepa as the villainous Crassus and Nina Timofeeva as the vampish Aegina, each dancer a renowned star of the famed Bolshoi Ballet at the time. This ballet-drama is a Soviet-Era vision of the much depicted uprising by Roman slaves, a grand cinematic spectacle, loaded with drama, romance and heroics to a score by Aram Khachaturian.

The epic Spartacus also inaugurates the upcoming series “Envisioning Russia : A Century of Filmmaking” (January 25 – February 12, 2008) which includes films from virtually every decade of Russian cinema and demonstrates its undeniable power and importance in the world. Co-presented with Seagull Films, the line-up of highlights includes films by notable directors such as Konchalovsky, Tarkovsky, Shepitko and Panfilov, as well as some earlier examples from the 20’s and 30’s, including a hilarious musical, “Vesoloye Rybata” (“Jolly Fellows”) that shows that Hollywood did not have a monopoly on this beloved genre.

Thinking of gladiator movies, we googled for some information and came across a very entertaining writer Richard von Busack who allowed us to reprint some of his work below.

“Roman Charges. The revival of the gladiator epic says as much about American politics as it does about ancient history.”

“In youth, the idea that there was once an age of heroes with swords and shields is picked up second-hand, like gossip. As always, that peerless source of forbidden information, the movies, filled in the details. As a kid, I was unable to tell the difference between movies and news broadcasts anymore than I could tell the difference between a painting and a photograph. How was I to know that gladiator movies weren’t newsreels?”

“Cinematically speaking, gladiators have been pushing up the gladioluses for four decades–the roots of both words are the same, no surprise to anyone who’s seen the “little sword” of a gladiolus shoot piercing the ground. These films were once inescapable, on “Gladiator Wednesdays” on KTVU or at “50-cent matinees’.”

“Most of these 150 or so films fit Charlton Heston’s definition of gladiator spectacles: “The easiest kind of movie to make badly.” As with science fiction movies, the good ones were great and the bad ones were better. Still, these gladiator films often proved to be more historically accurate than the Westerns and costume dramas of the time.”

“Jon Solomon, a classics professor from Columbia University who wrote the best book on the subject, The Ancient World in the Cinema (Barnes, 1978), praises the way the films summed up “the power, complexity and excitement of ancient life … respecting a money-paying audience as well as the heritage of mankind.”

“Gladiators count as one of the good parts of history, the part that can wake up a sleepy classroom. The gladiator picture provides the average American’s only exposure to the ancient world. At best, the gladiator movie presents a quick idea of how the Roman Empire looked and worked–and didn’t work.”

“Broad-sword conflict is always good for thrills, but the movie-going experience is deepened by the memory of one of the most famous of Roman tags: the poet Horace’s “Mutato nomie de te fabula narratur“–“change the names, and that story is about YOU!”

To read the full article of Richard von Busack on-line, visit www.metroactive.com/papers/metro/05.04.00/cover/gladiator1-0018.html

FLAMENCO AT 5:15

notes by director Cynthia Scott

From childhood I had been enthralled with the beauty and impossibility of ballet dancing. Years later a fortuitous moment at the National Film Board of Canada arose. A number of us were asked to work on a group of film documents about various dance companies in Canada. I was assigned the National Ballet of Canada, a company renowned internationally. I chose to watch and film one amazing rising star – a young black American who could leap higher than Barishnikov. His grace and line was beautiful to watch, but he was not very tall and the color of his skin in those days raised questions about how he could take a lead in one of the traditional full length ballets. Those issues are now long gone. His name was Kevin Pugh and his passion for the unachievable and the sublime moved me very much.

Thus sometime later I proposed to the NFB to make a documentary about how a ballet dancer comes into existence – observing young children starting out at the National Ballet School of Canada (one of the greatest schools in the world) and then watching each older group until finally settling on the now honed senior students waiting to graduate and become new stars in companies around the world. Funds were requested to do an initial two weeks research. I traveled by train from Montreal to Toronto in a January that was cringing in freezing blizzards. I went to classes from 9 in the morning to 5pm. All ages, all levels. Within a week my mind had blurred, slurred. Everything looked the same. I was surrounded by beautiful young bodies working so impossibly hard but I saw no line into a story, I could find no film. I was a hopeless failure as a filmmaker.

From the beginning of my visit, teachers, administrators had said to me excitedly “Susana is here! She has just arrived. You must go to one of her classes.” When I asked who this person was I was told she was a flamenco teacher from Spain who came each winter to work with the senior students. I was continually encouraged to treat myself to one of her classes but I dutifully assured everyone I was there to discover a film about the making of a ballet dancer and flamenco was not part of my research. By the beginning of the second week my bewilderment and sense of failure (“I can’t find a film here!!!”) had increased to the point of psychic exhaustion, so for escape from my depression and worries I wandered down to the class which started at 5:15 each evening. This was the last class at the end of a very long day for the young dancers. (I later was told that the then head and founder of the school, Betty Oliphant, had encountered Susana somewhere in Europe and thought she was just what her exhausted, overextended, overstressed senior students needed to momentarily free them from the discipline of classical dance, particularly since they were now overwhelmed by the competitive demanding rigors of the final months before graduating.)

Outside the arched studio windows it was already dark and snow was swirling around the street lamps. Inside, gazelle-like young dancers were excitedly pulling tight jeans up over their leotards. Instead of looking exhausted and spent from their ruthlessly demanding day, they were all smiles as they fastened their shiny black shoes with heels and drummed a few tentative staccato sounds with their feet. There was something invigorating in the air, like the effect one feels on hearing an orchestra warming up.

And then a silver haired tall man with an infectious smile appeared and sat down at the piano. The students gathered round Antonio, the life partner of Susana. The first section of the class was his. He was teaching “palmas” – the different sounds and techniques of hand clapping, as well as many, many different types of rhythms. Within moments my own palms felt unbearably itchy. I wanted to clap along with them. The complexity of the beats was impossible. Try as I might I could not master them in my head and yet all these dancers picked them up very quickly. Eventually Antonio was playing glorious flamenco melodies on the piano while the students joyously clapped out the palmas. Behind them suddenly appeared a tall black haired woman dressed in plain dark trousers and a top. Her hands were on her hips. She was watching them and smiling. An astonishing smile! Wrinkles radiated out from around her eyes like sunbeams.

The students assembled in lines behind her. Susana beat out a one simple slow step with a clarity and power of sound I had never heard before. The students repeated it. Then another and another — slowly progressing in speed and complexity. I was riveted and deeply thrilled by the sounds I was hearing. Now also my soles were itchy, longing to feel these sound patterns through my own feet. In ballet, the first class of every day, school or company is called the “barre.” The dancers work through a progression of the fundamental classical movements. It is a very beautiful event to watch because the movements are so pure and perfect. Susana had created a kind of “barre” of Flamenco steps. What I did not know that evening was that she was continually adding new steps, new rhythms and these senior students, by now very trained in musicality could pick her steps up almost instantly. Later she worked with them, actually teaching them particular choreography. I was beside myself with pleasure. So were the students.

For the rest of the week I ended each day of research observing Susana and Antonio’s life inspiring class. And like all those wise ones, they may be teaching about a specific subject but their wisdom makes the teaching extraordinarily broad and profound. Susana was teaching a way of being, a way of living, a way of truth. The flamenco was irresistible, but the profoundness of her being was searing. All who came under her spell will never forget her.

But I returned to Montreal very depressed and bewildered that I had not found a concept for a film about how one becomes a dancer. A few days later in the middle of the night I woke with the classical “eureka.” I had not found the film I was looking for but I had stumbled upon something else that was most extraordinary. The documentary FLAMENCO AT 5:15 came into existence.

The space was lit with lights shining through the windows from outside. This allowed complete freedom of movement for the dancers and the great cinematographer Paul Cowan. As flamenco is all about spontaneous response, we worked out a way for Susana to always be introducing new steps and movements so the students would continue to feel alive and excited. We filmed for four days.

Cynthia Scott has made three films that reflect her interest in dance: “For the Love of Dance” (1981), “Gala” (1982) and “Flamenco at 5:15,” which won the Oscar for best documentary short in 1984.

From childhood I had been enthralled with the beauty and impossibility of ballet dancing. Years later a fortuitous moment at the National Film Board of Canada arose. A number of us were asked to work on a group of film documents about various dance companies in Canada. I was assigned the National Ballet of Canada, a company renowned internationally. I chose to watch and film one amazing rising star – a young black American who could leap higher than Barishnikov. His grace and line was beautiful to watch, but he was not very tall and the color of his skin in those days raised questions about how he could take a lead in one of the traditional full length ballets. Those issues are now long gone. His name was Kevin Pugh and his passion for the unachievable and the sublime moved me very much.

Thus sometime later I proposed to the NFB to make a documentary about how a ballet dancer comes into existence – observing young children starting out at the National Ballet School of Canada (one of the greatest schools in the world) and then watching each older group until finally settling on the now honed senior students waiting to graduate and become new stars in companies around the world. Funds were requested to do an initial two weeks research. I traveled by train from Montreal to Toronto in a January that was cringing in freezing blizzards. I went to classes from 9 in the morning to 5pm. All ages, all levels. Within a week my mind had blurred, slurred. Everything looked the same. I was surrounded by beautiful young bodies working so impossibly hard but I saw no line into a story, I could find no film. I was a hopeless failure as a filmmaker.

From the beginning of my visit, teachers, administrators had said to me excitedly “Susana is here! She has just arrived. You must go to one of her classes.” When I asked who this person was I was told she was a flamenco teacher from Spain who came each winter to work with the senior students. I was continually encouraged to treat myself to one of her classes but I dutifully assured everyone I was there to discover a film about the making of a ballet dancer and flamenco was not part of my research. By the beginning of the second week my bewilderment and sense of failure (“I can’t find a film here!!!”) had increased to the point of psychic exhaustion, so for escape from my depression and worries I wandered down to the class which started at 5:15 each evening. This was the last class at the end of a very long day for the young dancers. (I later was told that the then head and founder of the school, Betty Oliphant, had encountered Susana somewhere in Europe and thought she was just what her exhausted, overextended, overstressed senior students needed to momentarily free them from the discipline of classical dance, particularly since they were now overwhelmed by the competitive demanding rigors of the final months before graduating.)

Outside the arched studio windows it was already dark and snow was swirling around the street lamps. Inside, gazelle-like young dancers were excitedly pulling tight jeans up over their leotards. Instead of looking exhausted and spent from their ruthlessly demanding day, they were all smiles as they fastened their shiny black shoes with heels and drummed a few tentative staccato sounds with their feet. There was something invigorating in the air, like the effect one feels on hearing an orchestra warming up.

And then a silver haired tall man with an infectious smile appeared and sat down at the piano. The students gathered round Antonio, the life partner of Susana. The first section of the class was his. He was teaching “palmas” – the different sounds and techniques of hand clapping, as well as many, many different types of rhythms. Within moments my own palms felt unbearably itchy. I wanted to clap along with them. The complexity of the beats was impossible. Try as I might I could not master them in my head and yet all these dancers picked them up very quickly. Eventually Antonio was playing glorious flamenco melodies on the piano while the students joyously clapped out the palmas. Behind them suddenly appeared a tall black haired woman dressed in plain dark trousers and a top. Her hands were on her hips. She was watching them and smiling. An astonishing smile! Wrinkles radiated out from around her eyes like sunbeams.

The students assembled in lines behind her. Susana beat out a one simple slow step with a clarity and power of sound I had never heard before. The students repeated it. Then another and another — slowly progressing in speed and complexity. I was riveted and deeply thrilled by the sounds I was hearing. Now also my soles were itchy, longing to feel these sound patterns through my own feet. In ballet, the first class of every day, school or company is called the “barre.” The dancers work through a progression of the fundamental classical movements. It is a very beautiful event to watch because the movements are so pure and perfect. Susana had created a kind of “barre” of Flamenco steps. What I did not know that evening was that she was continually adding new steps, new rhythms and these senior students, by now very trained in musicality could pick her steps up almost instantly. Later she worked with them, actually teaching them particular choreography. I was beside myself with pleasure. So were the students.

For the rest of the week I ended each day of research observing Susana and Antonio’s life inspiring class. And like all those wise ones, they may be teaching about a specific subject but their wisdom makes the teaching extraordinarily broad and profound. Susana was teaching a way of being, a way of living, a way of truth. The flamenco was irresistible, but the profoundness of her being was searing. All who came under her spell will never forget her.

But I returned to Montreal very depressed and bewildered that I had not found a concept for a film about how one becomes a dancer. A few days later in the middle of the night I woke with the classical “eureka.” I had not found the film I was looking for but I had stumbled upon something else that was most extraordinary. The documentary FLAMENCO AT 5:15 came into existence.

The space was lit with lights shining through the windows from outside. This allowed complete freedom of movement for the dancers and the great cinematographer Paul Cowan. As flamenco is all about spontaneous response, we worked out a way for Susana to always be introducing new steps and movements so the students would continue to feel alive and excited. We filmed for four days.

Cynthia Scott has made three films that reflect her interest in dance: “For the Love of Dance” (1981), “Gala” (1982) and “Flamenco at 5:15,” which won the Oscar for best documentary short in 1984.

Both films last about 30 minutes and are in black and white with stark side lighting. But “Bare Handed” is considerably more ambitious filmically and theatrically. Again, Noiret stalks and writhes about in black. But this time there are ever-present, sometimes large-than-life projections on a screen behind her and, more touchingly, an old man with quivering hands and elegant, shaky handwriting who periodically appears from behind the screen, watching silently. His words and her whispering into his ear circle back, over and over, to dreams. The old man turns out – when you read the credits – to be Joseph Noiret.

I found “Bare Handed” – the French title, “A Mains Nues,” means exactly the same thing but is somehow more sexy and mysterious – compelling from start to finish. Without knowing the tastes of the 2007 jury, I can only speculate that Knauff’s entry failed to make the cut for the jury prize because it seemed more theatrical and filmic and less choreographic – more a Knauff film than a Noiret film.

Of course this is a false dichotomy, especially in the closely-linked intersections of dance, theater and film in Europe today. But American dance critics seem still more closely wedded to “pure” dance abstraction in the Balanchine-Cunningham mode. The very notion of dance on camera suggests a marriage of those two art forms. But maybe there is still a bias here towards film as a handmaiden of dance, better serving the purposes of documentation and celebration than incorporating movement into film for more overtly cinematic purposes.

Then again, “The Cost of Living,” for all its choreographic brilliance, was plenty theatrical. So maybe this time around my taste simply differed from the Dance on Camera jury. “Bare Handed” is still worth seeking out. It’s a powerful work, whatever its genre may be.

John Rockwell will be a member of the Dance on Camera Festival 2008 Jury, along with Alla Kovgan, David Michalek, Gerald Busby, and Lana Wilson.

SPARTACUS opens Dance on Camera Festival 2008

Both films last about 30 minutes and are in black and white with stark side lighting. But “Bare Handed” is considerably more ambitious filmically and theatrically. Again, Noiret stalks and writhes about in black. But this time there are ever-present, sometimes large-than-life projections on a screen behind her and, more touchingly, an old man with quivering hands and elegant, shaky handwriting who periodically appears from behind the screen, watching silently. His words and her whispering into his ear circle back, over and over, to dreams. The old man turns out – when you read the credits – to be Joseph Noiret.

I found “Bare Handed” – the French title, “A Mains Nues,” means exactly the same thing but is somehow more sexy and mysterious – compelling from start to finish. Without knowing the tastes of the 2007 jury, I can only speculate that Knauff’s entry failed to make the cut for the jury prize because it seemed more theatrical and filmic and less choreographic – more a Knauff film than a Noiret film.

Of course this is a false dichotomy, especially in the closely-linked intersections of dance, theater and film in Europe today. But American dance critics seem still more closely wedded to “pure” dance abstraction in the Balanchine-Cunningham mode. The very notion of dance on camera suggests a marriage of those two art forms. But maybe there is still a bias here towards film as a handmaiden of dance, better serving the purposes of documentation and celebration than incorporating movement into film for more overtly cinematic purposes.

Then again, “The Cost of Living,” for all its choreographic brilliance, was plenty theatrical. So maybe this time around my taste simply differed from the Dance on Camera jury. “Bare Handed” is still worth seeking out. It’s a powerful work, whatever its genre may be.

John Rockwell will be a member of the Dance on Camera Festival 2008 Jury, along with Alla Kovgan, David Michalek, Gerald Busby, and Lana Wilson.

SPARTACUS opens Dance on Camera Festival 2008