Bienvenida Matias joins DFA as Executive Director

After an extensive search, the Board of Directors of DFA is delighted to introduce its new Executive Director, Bienvenida (Beni) Matias. Beni comes to DFA with years of experience: as Executive Director for the Association of Hispanic Arts, the Association of Independent Video and Filmmakers (AIVF), and the Center for Arts Criticism. As a docu- mentary film producer/director she has men- tored filmmakers and created programs aimed at strengthening production skills, and serves on the Board of Directors of the National Association for Latino Independent Producers.

Beni’s film and fund-raising background, her ability to articulate goals and build a path to reach them complement the gifts of our long-time Artistic Director, Deirdre Towers. We hope you’ll join us at the Annual Meeting on October 14, 2010, where you’ll get a chance to meet Beni, hear a bit more about DFA’s re-structuring and vote on DFA’s revised Bylaws.

Beni Matias writes, “The first time I saw WEST SIDE STORY I was horrified and fascinated at the same time. I was horrified at its depiction of Puerto Ricans as gang-bangers, a continued stereotype of our community, the newest residents of New York. The fascination was with the dancing that told a complex story of young people vying for a place to call their own. The camera movements and music encapsulates the intensity of emotions with the city as an integral part of the story.

WEST SIDE STORY stays with me as a reminder of the racism Puerto Ricans have endured. But, Robbins’ choreography and Bernstein’s music has also sticks with me. I recognize Robbins’ movement when I viewed NEW YORK EXPORT: OPUS JAZZ. I know what the dancers will do once they start leaning forward with one shoulder lower than the other moving towards camera. It brings back memories and creates new ones.

Dance and film are two art forms that rely on collaboration. Together, they create a powerful union of energy, emotions and motions. Dance films, from experimental shorts to Hollywood blockbusters, speak to diverse audiences. And, audience members, such as me, will carry these images for many years.

It is my pleasure to join DFA as Executive Director. As a documentary filmmaker who loves dance, I will work hard to strengthen DFA’s programs to best serve the needs of the membership, to advance the development of dance films, and to find new audience for the incredible work created by our members

EMPAC: Commissioning Dance Movies

Applicants for the first round of 2010-2011 cycle have learned by now which were invited to submit a more detailed proposal. Commissions will be announced in July, offering from $7,000–$30,000. Depending on the nature of the project, the following resources, in addition to the funding, may be provided or facilitated by EMPAC: Access to studio space for rehearsals and shooting; Access to equipment for use in the EMPAC facility; Post-production: access to professional video and audio editing and mastering equipment; Technical support from stage technologies, audio and video engineers, and other staff at EMPAC.

This fall, EMPAC will present the winners of the 2009-2010 commission:

ANATOMY OF MELANCHOLY (Nuria Fragoso, Mexico, 10′ ) Two contrasting spaces – one light and open, the other constrained and dark – form the environment for dancers moving against expectation.

HOOP (Marites Carino, Canada, 4′) A woman floats in a black void, swinging through shafts of light, keeping in perpetual motion an incandescent and familiar circular childhood toy.

MO-SO (Kasumi, USA, 12′ – three-channel video installation) Fragmentary and symbolically charged images serve as a basis for improvisation. The footage is then fed back into the polyphonic narrative, musical and choreographic structure.

Q (Rajendra Serber, USA, 12′) In this exploration of urban isolation, three men trace their solitary paths through empty streets at night. When the strangers try to pass, they become locked in anonymous antagonism.

THE CLOSER ONE GETS, THE LESS ONE SEES (Valeria Valenzuela Brazil, 12′) Intervention in the lives of three jugglers/beggars, who get together at traf- fic lights in Rio de Janeiro, transforms the objective action of their juggling into the abstract vocabulary of contemporary dance.

Selected from 69 applications, of which 28 were short-listed, the 5 funded projects represent the third round of awards given out through the EMPAC DANCE MOViES Commission.

DFA awards post-production grants to 4

A panel, made up of critic Robert Johnson, filmmaker Amy Greenfield, pro- ducer Elena Martinez met to review 17 DFA’s post-production grant sub- missions. Thanks to donations from member Anne Bass and DFA’s Board, the funding pool this year was increased from $2,500 to $2,800. The panelists were unanimous in recommending funding for four projects, as follows:

• WHERE GOD SLEEPS Kathy Craven: Director, Budget: $201,440, DFA Award: $800 Documentary: 60 minutes. Filmmaker located in Orlando, Florida Sidiki Conde lost the use of his legs at age 14. Soon after, he literally pulled his body into the bush of his remote West African village. He watched ducks moving back and forth on their webbed feet and slowly he learned to pull his body upright. He taught himself to dance on his hands until he was dancing with steps true to traditional tribal rhythms.

• FIRST DANCE Chisa Hidaka: director; Budget: $15,701; DFA Award $400 Experimental short. Filmmaker located in New York City A short film of an underwater dance between a human and wild Pacific Spinner Dolphins. FIRST DANCE by the Dolphin Dance Project, brings audiences interested in dolphins and the ocean to contemporary dance, and dance audiences to marine biology.

• THE LIFE OF MARTHA HILL Greg Vander Veer: Director Vernon Scott, Coordinating Producer; Budget: $207,492; DFA Award $800 Documentary, full-length. A project of Martha Hill Foundation, New York Martha Hill had a life-long dedication to revolutionizing dance education as she struggled to solidify modern dance as a legitimate art form. The film- makers promise to complete a provocative portrait of the career and vision that played an immense and integral role in the inception and development of the American modern dance movement.

• FEELINGS ARE FACTS: THE LIFE OF YVONNE RAINER Director: Jack Walsh; Budget: $476,551; DFA Award $800 Documentary, full-length. Filmmaker located in San Francisco Yvonne Rainer has been a maverick in the fields of dance and film for more than four decades. Over the course of her career, she revolutionized modern dance, created what came to be known as performance art, and reintroduced narrative storytelling into experimental filmmaking. She did this at a time when the challenges faced by women trying to establish careers in the art world were formidable.

From choreographer to director: a natural evolution

by Gabri Christa

I used to say that I was in transition. Yes, I was still dancing and choreographing, but also making films and directing. After a year of just directing projects for both stage and screen, I look back at the last 8 years since my first film and see that everything I have done in my career was a preparation for this phase in my life.

Beni’s film and fund-raising background, her ability to articulate goals and build a path to reach them complement the gifts of our long-time Artistic Director, Deirdre Towers. We hope you’ll join us at the Annual Meeting on October 14, 2010, where you’ll get a chance to meet Beni, hear a bit more about DFA’s re-structuring and vote on DFA’s revised Bylaws.

Beni Matias writes, “The first time I saw WEST SIDE STORY I was horrified and fascinated at the same time. I was horrified at its depiction of Puerto Ricans as gang-bangers, a continued stereotype of our community, the newest residents of New York. The fascination was with the dancing that told a complex story of young people vying for a place to call their own. The camera movements and music encapsulates the intensity of emotions with the city as an integral part of the story.

WEST SIDE STORY stays with me as a reminder of the racism Puerto Ricans have endured. But, Robbins’ choreography and Bernstein’s music has also sticks with me. I recognize Robbins’ movement when I viewed NEW YORK EXPORT: OPUS JAZZ. I know what the dancers will do once they start leaning forward with one shoulder lower than the other moving towards camera. It brings back memories and creates new ones.

Dance and film are two art forms that rely on collaboration. Together, they create a powerful union of energy, emotions and motions. Dance films, from experimental shorts to Hollywood blockbusters, speak to diverse audiences. And, audience members, such as me, will carry these images for many years.

It is my pleasure to join DFA as Executive Director. As a documentary filmmaker who loves dance, I will work hard to strengthen DFA’s programs to best serve the needs of the membership, to advance the development of dance films, and to find new audience for the incredible work created by our members

EMPAC: Commissioning Dance Movies

Applicants for the first round of 2010-2011 cycle have learned by now which were invited to submit a more detailed proposal. Commissions will be announced in July, offering from $7,000–$30,000. Depending on the nature of the project, the following resources, in addition to the funding, may be provided or facilitated by EMPAC: Access to studio space for rehearsals and shooting; Access to equipment for use in the EMPAC facility; Post-production: access to professional video and audio editing and mastering equipment; Technical support from stage technologies, audio and video engineers, and other staff at EMPAC.

This fall, EMPAC will present the winners of the 2009-2010 commission:

ANATOMY OF MELANCHOLY (Nuria Fragoso, Mexico, 10′ ) Two contrasting spaces – one light and open, the other constrained and dark – form the environment for dancers moving against expectation.

HOOP (Marites Carino, Canada, 4′) A woman floats in a black void, swinging through shafts of light, keeping in perpetual motion an incandescent and familiar circular childhood toy.

MO-SO (Kasumi, USA, 12′ – three-channel video installation) Fragmentary and symbolically charged images serve as a basis for improvisation. The footage is then fed back into the polyphonic narrative, musical and choreographic structure.

Q (Rajendra Serber, USA, 12′) In this exploration of urban isolation, three men trace their solitary paths through empty streets at night. When the strangers try to pass, they become locked in anonymous antagonism.

THE CLOSER ONE GETS, THE LESS ONE SEES (Valeria Valenzuela Brazil, 12′) Intervention in the lives of three jugglers/beggars, who get together at traf- fic lights in Rio de Janeiro, transforms the objective action of their juggling into the abstract vocabulary of contemporary dance.

Selected from 69 applications, of which 28 were short-listed, the 5 funded projects represent the third round of awards given out through the EMPAC DANCE MOViES Commission.

DFA awards post-production grants to 4

A panel, made up of critic Robert Johnson, filmmaker Amy Greenfield, pro- ducer Elena Martinez met to review 17 DFA’s post-production grant sub- missions. Thanks to donations from member Anne Bass and DFA’s Board, the funding pool this year was increased from $2,500 to $2,800. The panelists were unanimous in recommending funding for four projects, as follows:

• WHERE GOD SLEEPS Kathy Craven: Director, Budget: $201,440, DFA Award: $800 Documentary: 60 minutes. Filmmaker located in Orlando, Florida Sidiki Conde lost the use of his legs at age 14. Soon after, he literally pulled his body into the bush of his remote West African village. He watched ducks moving back and forth on their webbed feet and slowly he learned to pull his body upright. He taught himself to dance on his hands until he was dancing with steps true to traditional tribal rhythms.

• FIRST DANCE Chisa Hidaka: director; Budget: $15,701; DFA Award $400 Experimental short. Filmmaker located in New York City A short film of an underwater dance between a human and wild Pacific Spinner Dolphins. FIRST DANCE by the Dolphin Dance Project, brings audiences interested in dolphins and the ocean to contemporary dance, and dance audiences to marine biology.

• THE LIFE OF MARTHA HILL Greg Vander Veer: Director Vernon Scott, Coordinating Producer; Budget: $207,492; DFA Award $800 Documentary, full-length. A project of Martha Hill Foundation, New York Martha Hill had a life-long dedication to revolutionizing dance education as she struggled to solidify modern dance as a legitimate art form. The film- makers promise to complete a provocative portrait of the career and vision that played an immense and integral role in the inception and development of the American modern dance movement.

• FEELINGS ARE FACTS: THE LIFE OF YVONNE RAINER Director: Jack Walsh; Budget: $476,551; DFA Award $800 Documentary, full-length. Filmmaker located in San Francisco Yvonne Rainer has been a maverick in the fields of dance and film for more than four decades. Over the course of her career, she revolutionized modern dance, created what came to be known as performance art, and reintroduced narrative storytelling into experimental filmmaking. She did this at a time when the challenges faced by women trying to establish careers in the art world were formidable.

From choreographer to director: a natural evolution

by Gabri Christa

I used to say that I was in transition. Yes, I was still dancing and choreographing, but also making films and directing. After a year of just directing projects for both stage and screen, I look back at the last 8 years since my first film and see that everything I have done in my career was a preparation for this phase in my life.

Before I danced, I wrote and did Yoga. I was the editor for our high school paper, and published my first story. I went to Journalism School and found dance. During my days at the School for New Dance Development in Amsterdam, and also when I studied at the Rotterdamse Dans Akedemie, I wrote and worked in broadcast. I also worked on my first Feature film as an Assistant Producer for “Almacita di Desolato “a movie directed by Felix de Rooy with Ernest Dickerson as Director of Photography. I also acted a bit, mostly in commercials I even managed to become member of Screen Actors Guild.

I still learn through doing, watching, listening and asking for advice. I was lucky to find as my early collaborator Evann Siebens, a dancer turned film maker and – an even earlier support for my endeavors- in visionary, activist producer and filmmaker Warrington Hudlin, who gave me my first funding to make a short through his project: dvRepublic.

In my first my first dance films, I directed and choreographed and did everything else. About a year ago, I found myself wanting to make a narrative film, without dance. I was very excited when some projects came my way. In the last 9 months, I directed 2 music videos, one commercial, one evening length multi-media performance called “Fire & Fire,” that pre- miered at Symphony Space and a short narrative “Salon Day”, for Ripfest.

Each of these projects had a clear goal and a timeline. I had one guide- line: how do I best communicate the theme of this project and still have enough of a creative voice to make this an artistic process for myself?

I find my relationship with the Director of Photography (DP), extremely important. At first my main struggle was to communicate with a DP who didn’t come from the dance world. I took some time between my first three films and the more recent ones, to better understand how to direct. Director Charles Stone III shared with me some of his process in developing a work and his inspired style of talking to a DP. I now prepare a sketch-book: I cut out and copy anything that relates to what I want to do. I look for tone, style and angle. I find as many visuals as possible to facilitate collaboration between the DP and myself.

As a director, I see myself more as a coach or facilitator; to insure that everyone makes their best work. I ask many questions. To that end, I now collaborate with a choreographer, rather than choreographing myself. It helps me to have some distance. Keeping track of the big pic- ture is ultimately what best serves the work.

As a choreographer and director, I work mostly with original music. I also create most of the work before a composer comes in. I record live sounds to make the dance come as much alive as possible. Wind, steps, all of it is important. What was most enlightening was working on the music video I directed and conceived for Izaline Callister. The clear goal was to represent her lyrics with images driven by her text. See (youtube.com/watch?v=SVQusDAy6K8). Curaçao Tourism Bureau, which paid for the clip, required certain shots.

I really liked the limitations placed on me in this project – Curaçao Tourism Bureau, which paid for the clip, required certain shots – learned to find creative solutions without sacrificing the art. I had worked with a DP twice before but I had to keep getting out of my own way. The video for Izaline had great play; she won the Edison (Dutch Grammy) for World Music right after we finished.

In dance, “my” movement becomes so personal, so precious that I find it hard to see. I learn from the distance a screen provides. I am no longer all-important, the idea is. I learned most from screenwriter Marlaine Glucksman, who teaches screen writing and is also a director, to see and hear how a screenwriter clarifies the work and narrows it down to a theme. I found this to be almost too simple initially. As a dancer, I think in the unseen, my sense of narration is non linear and often not logical. With Marlaine I worked on one of my own ideas. I realized that I want to communicate after all.

With the Ripfest Film Project, the screenplay text provided the story. I discovered that within this limitation, there was so much freedom. Designing the shots, determining the color, time, costumes, tone, and angles with DP Ben Bloodwell helped me find my voice and vision.

Everyone around you from producer to DP, to actors to screenwriter to composer, all determine the movie. Within that group there is more wisdom and knowledge than I can find alone. A communal creative spirit, comes through. Within these confinements, I discovered that I could still have my own vision.

As I am working on my first narrative feature, I know the road will be filled with more questions and lessons. Yet within me I carry the dance, the riches it has brought me, the life and work tools it has given me, the fluidity. I could not have imagined a better preparation.

TETRO, a realization of a childhood dream

review by Amy Greenfield

Francis Ford Coppola’s self-financed film, TETRO, just out on dvd from Lions Gate Films, is a multi-leveled exploration of family, creativity, loss, recognition and redemption. The film’s narrative, shot in black and white, centers on the tortured writer, Tetro, played by Vincent Gallo. Flashbacks to key events in Tetro’s past in color and four ballet scenes purposefully recall Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger’s great dance opera film, THE TALES OF HOFFMAN, as well as their much more well-known, THE RED SHOES.

Coppola, with his can-do-anything cinematographer, Mihai Malaimari, shot the film in three styles. The realistic flashbacks are shot handheld documentary-like, with jagged, narrative cutting. The visionary dance scenes, which encapsulate Tetro’s hidden family-centered mysteries with poetic power, stylistically oppose the black-and-white, intimate, close-up world of the “present.” They are shot with stationary, barely cut long-shots in fantasy cyber sets (works of art themselves) and in rich color, recalling 1950s Technicolor used to shoot both THE TALES OF HOFFMAN and THE RED SHOES.

TETRO’s dvd “Special Feature” shows how meticulously the ballet scenes were conceived, how they operate within the narrative, stylistically and dramatically. They show what can’t be spoken of, what Tetro can’t escape from, what must come out. The color scenes lead to the unexpressed changes within him which come together in a powerful and moving denouement.

We see how Coppola’s techniques go back also to the early cinema genius, Georges Melies, and his “trick” films, with ballet dancers hanging in mid-air against hand-painted “sets.” Melies in the 19th century, Powell in the 20th century, and Coppola in the 21st digital century making dance “trick” films go far beyond tricks, to become cinema magic. The TETRO scenes were shot against blue screen then digitally placed in amazing sets. We see rehearsals of dance scenes and choreography, which unfortunately didn’t make it into the film. The dance scenes weren’t completed until most of the dramatic editing was completed.

The dance scenes, each only a few minutes or less, are woven inextricably into the film like a tapestry, one pattern woven and rewoven to lend a depth of meaning and emotional richness not possible by in a straight narrative. Coppola shows us how cine-dance can uncover, as a dream does, the essence of a psychological inner state within the realistic outer narrative. The stylized, surreal condensation of the ballet scenes; the precise long-shot framing, the hard-edged nature of ballet, the rich color etched against spare “painted” backgrounds, all enable us to experience how these past events are like tattoos bled into Tetro’s psyche. Their knife-like puncturing of the film gives wordless expression to Tetro’s mind being stabbed into recognition, change and finally a redemption of self and resumption of life.

The film is about Tetro estranged himself from his family, moving to Argentina, to become a writer. The story starts when many years later, his much younger brother, Benny, turns up at Tetro’s Buenos Aries apartment to find out about family mysteries. Tetros’s girlfriend when he was eighteen was a dancer whom we see dancing informally for his father, a famous, but tyrannical orchestral conductor, in their home to the music from THE TALES OF HOFFMAN.

Before I danced, I wrote and did Yoga. I was the editor for our high school paper, and published my first story. I went to Journalism School and found dance. During my days at the School for New Dance Development in Amsterdam, and also when I studied at the Rotterdamse Dans Akedemie, I wrote and worked in broadcast. I also worked on my first Feature film as an Assistant Producer for “Almacita di Desolato “a movie directed by Felix de Rooy with Ernest Dickerson as Director of Photography. I also acted a bit, mostly in commercials I even managed to become member of Screen Actors Guild.

I still learn through doing, watching, listening and asking for advice. I was lucky to find as my early collaborator Evann Siebens, a dancer turned film maker and – an even earlier support for my endeavors- in visionary, activist producer and filmmaker Warrington Hudlin, who gave me my first funding to make a short through his project: dvRepublic.

In my first my first dance films, I directed and choreographed and did everything else. About a year ago, I found myself wanting to make a narrative film, without dance. I was very excited when some projects came my way. In the last 9 months, I directed 2 music videos, one commercial, one evening length multi-media performance called “Fire & Fire,” that pre- miered at Symphony Space and a short narrative “Salon Day”, for Ripfest.

Each of these projects had a clear goal and a timeline. I had one guide- line: how do I best communicate the theme of this project and still have enough of a creative voice to make this an artistic process for myself?

I find my relationship with the Director of Photography (DP), extremely important. At first my main struggle was to communicate with a DP who didn’t come from the dance world. I took some time between my first three films and the more recent ones, to better understand how to direct. Director Charles Stone III shared with me some of his process in developing a work and his inspired style of talking to a DP. I now prepare a sketch-book: I cut out and copy anything that relates to what I want to do. I look for tone, style and angle. I find as many visuals as possible to facilitate collaboration between the DP and myself.

As a director, I see myself more as a coach or facilitator; to insure that everyone makes their best work. I ask many questions. To that end, I now collaborate with a choreographer, rather than choreographing myself. It helps me to have some distance. Keeping track of the big pic- ture is ultimately what best serves the work.

As a choreographer and director, I work mostly with original music. I also create most of the work before a composer comes in. I record live sounds to make the dance come as much alive as possible. Wind, steps, all of it is important. What was most enlightening was working on the music video I directed and conceived for Izaline Callister. The clear goal was to represent her lyrics with images driven by her text. See (youtube.com/watch?v=SVQusDAy6K8). Curaçao Tourism Bureau, which paid for the clip, required certain shots.

I really liked the limitations placed on me in this project – Curaçao Tourism Bureau, which paid for the clip, required certain shots – learned to find creative solutions without sacrificing the art. I had worked with a DP twice before but I had to keep getting out of my own way. The video for Izaline had great play; she won the Edison (Dutch Grammy) for World Music right after we finished.

In dance, “my” movement becomes so personal, so precious that I find it hard to see. I learn from the distance a screen provides. I am no longer all-important, the idea is. I learned most from screenwriter Marlaine Glucksman, who teaches screen writing and is also a director, to see and hear how a screenwriter clarifies the work and narrows it down to a theme. I found this to be almost too simple initially. As a dancer, I think in the unseen, my sense of narration is non linear and often not logical. With Marlaine I worked on one of my own ideas. I realized that I want to communicate after all.

With the Ripfest Film Project, the screenplay text provided the story. I discovered that within this limitation, there was so much freedom. Designing the shots, determining the color, time, costumes, tone, and angles with DP Ben Bloodwell helped me find my voice and vision.

Everyone around you from producer to DP, to actors to screenwriter to composer, all determine the movie. Within that group there is more wisdom and knowledge than I can find alone. A communal creative spirit, comes through. Within these confinements, I discovered that I could still have my own vision.

As I am working on my first narrative feature, I know the road will be filled with more questions and lessons. Yet within me I carry the dance, the riches it has brought me, the life and work tools it has given me, the fluidity. I could not have imagined a better preparation.

TETRO, a realization of a childhood dream

review by Amy Greenfield

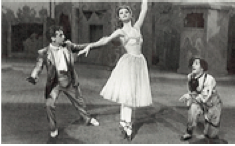

Francis Ford Coppola’s self-financed film, TETRO, just out on dvd from Lions Gate Films, is a multi-leveled exploration of family, creativity, loss, recognition and redemption. The film’s narrative, shot in black and white, centers on the tortured writer, Tetro, played by Vincent Gallo. Flashbacks to key events in Tetro’s past in color and four ballet scenes purposefully recall Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger’s great dance opera film, THE TALES OF HOFFMAN, as well as their much more well-known, THE RED SHOES.

Coppola, with his can-do-anything cinematographer, Mihai Malaimari, shot the film in three styles. The realistic flashbacks are shot handheld documentary-like, with jagged, narrative cutting. The visionary dance scenes, which encapsulate Tetro’s hidden family-centered mysteries with poetic power, stylistically oppose the black-and-white, intimate, close-up world of the “present.” They are shot with stationary, barely cut long-shots in fantasy cyber sets (works of art themselves) and in rich color, recalling 1950s Technicolor used to shoot both THE TALES OF HOFFMAN and THE RED SHOES.

TETRO’s dvd “Special Feature” shows how meticulously the ballet scenes were conceived, how they operate within the narrative, stylistically and dramatically. They show what can’t be spoken of, what Tetro can’t escape from, what must come out. The color scenes lead to the unexpressed changes within him which come together in a powerful and moving denouement.

We see how Coppola’s techniques go back also to the early cinema genius, Georges Melies, and his “trick” films, with ballet dancers hanging in mid-air against hand-painted “sets.” Melies in the 19th century, Powell in the 20th century, and Coppola in the 21st digital century making dance “trick” films go far beyond tricks, to become cinema magic. The TETRO scenes were shot against blue screen then digitally placed in amazing sets. We see rehearsals of dance scenes and choreography, which unfortunately didn’t make it into the film. The dance scenes weren’t completed until most of the dramatic editing was completed.

The dance scenes, each only a few minutes or less, are woven inextricably into the film like a tapestry, one pattern woven and rewoven to lend a depth of meaning and emotional richness not possible by in a straight narrative. Coppola shows us how cine-dance can uncover, as a dream does, the essence of a psychological inner state within the realistic outer narrative. The stylized, surreal condensation of the ballet scenes; the precise long-shot framing, the hard-edged nature of ballet, the rich color etched against spare “painted” backgrounds, all enable us to experience how these past events are like tattoos bled into Tetro’s psyche. Their knife-like puncturing of the film gives wordless expression to Tetro’s mind being stabbed into recognition, change and finally a redemption of self and resumption of life.

The film is about Tetro estranged himself from his family, moving to Argentina, to become a writer. The story starts when many years later, his much younger brother, Benny, turns up at Tetro’s Buenos Aries apartment to find out about family mysteries. Tetros’s girlfriend when he was eighteen was a dancer whom we see dancing informally for his father, a famous, but tyrannical orchestral conductor, in their home to the music from THE TALES OF HOFFMAN.

THE TALES OF HOFFMAN is one of the most amazing cinema ballets ever made, eclipsed by the more famous and more popularly conceived Powell-Pressberger, THE RED SHOES. THE TALES OF HOFFMANN is virtually all dance and music, a transformation of the opera. As Michael Powell was the director and Emeric Pressburger the screenwriter, the vision of the dance scenes in THE RED SHOES and THE TALES OF HOFFMANN can be attributed to Powell.

Last season, at the reception of the New York Director’s Guild opening of TETRO, I spoke with Coppola about his own dance scenes. Coppola told me TETRO’s dance scenes spring from childhood events central to his identity as a filmmaker. Coppola’s older brother took him to see THE RED SHOES and THE TALES OF HOFFMANN (I believe repeatedly) when he was a young boy. He was enchanted and possessed by them. He made up his own dance scenes in his imagination. Through TETRO, he finally realized a childhood dream, and recovered precious childhood memories. The first ballet scene parallels Coppola’s memories. Benny adoringly recalls to his older brother, Tetro, how he would take him to see THE RED SHOES and THE TALES OF HOFFMANN when Benny was little. The film then cuts to a scene actually from THE TALES OF HOFFMANN itself – the climax of the first part, based on the Coppelia/Coppelius story, played by Moira Shearer as Coppelia. She is comically beautifully, horribly torn limb from limb and “decapitated” by Coppelius. Later, Benny finds out in a letter Tetro has kept, that the eighteen year old Tetro’s dancer girlfriend wrote to him that she “feels like Coppelia being torn apart.”

TETRO was shot in Argentina with the ballet scenes choreographed by Argentine Anna Maria Steckelman and performed by her company. The third ballet scene, my favorite, is embedded in the narrative in a special way. Earlier in the film we’ve seen a realistic flashback of Tetro’s mother’s die in a car accident. Right before the ballet, we see Tetro’s eyes in extreme close-up staring straight into blinding light, which flares off the glacier landscape of Patagonia. Cut to the ballet scene: a duet to repre- sent Tetro and his mother. The blanched Patagonia landscape turns into an artificially (recalling early cinema yet digitally constructed) night scene. The light bursting off the glaciers turn into two headlights of an unseen car, with the dancers rolling out onto a line of blood on the road. This 1 1⁄2 minute scene, set to music of female voice and a heart beat, in the spectral landscape, shot from extreme high and low angles, could be a miniature ballet film gem in and of itself.

The scene becomes Tetro’s trance-like staring into the haunted darkness and blinding light within himself. His mind transforms the reality of death into a scene of transcendence, like a sacred rite, with the mother coming alive as a red-robed spirit wafting up into the black air, as Tetro is left below on the line of blood, reaching after her. The color red being symbol- ic not only of blood, but of blood ties.

All the dance scenes not only metaphorically image the past, but also presage what we don’t know about that past that finally is revealed at the end of the film. Coppola shows how film dance in a narrative film can operate on a level Jung wrote about – that key visions and dreams contain the power to transform consciousness in a person’s struggle to renew his/her health and life.

Amy Greenfield has made almost forty dance films, videotapes, holograms, multi-media performances and installations. Her work has been shown at such festivals as the Berlin, London, Edinburgh, New York, Houston, in one woman and group shows at the Museum of Modern Art, The National Gallery Of Art, and The Whitney Museum.

THE TALES OF HOFFMAN is one of the most amazing cinema ballets ever made, eclipsed by the more famous and more popularly conceived Powell-Pressberger, THE RED SHOES. THE TALES OF HOFFMANN is virtually all dance and music, a transformation of the opera. As Michael Powell was the director and Emeric Pressburger the screenwriter, the vision of the dance scenes in THE RED SHOES and THE TALES OF HOFFMANN can be attributed to Powell.

Last season, at the reception of the New York Director’s Guild opening of TETRO, I spoke with Coppola about his own dance scenes. Coppola told me TETRO’s dance scenes spring from childhood events central to his identity as a filmmaker. Coppola’s older brother took him to see THE RED SHOES and THE TALES OF HOFFMANN (I believe repeatedly) when he was a young boy. He was enchanted and possessed by them. He made up his own dance scenes in his imagination. Through TETRO, he finally realized a childhood dream, and recovered precious childhood memories. The first ballet scene parallels Coppola’s memories. Benny adoringly recalls to his older brother, Tetro, how he would take him to see THE RED SHOES and THE TALES OF HOFFMANN when Benny was little. The film then cuts to a scene actually from THE TALES OF HOFFMANN itself – the climax of the first part, based on the Coppelia/Coppelius story, played by Moira Shearer as Coppelia. She is comically beautifully, horribly torn limb from limb and “decapitated” by Coppelius. Later, Benny finds out in a letter Tetro has kept, that the eighteen year old Tetro’s dancer girlfriend wrote to him that she “feels like Coppelia being torn apart.”

TETRO was shot in Argentina with the ballet scenes choreographed by Argentine Anna Maria Steckelman and performed by her company. The third ballet scene, my favorite, is embedded in the narrative in a special way. Earlier in the film we’ve seen a realistic flashback of Tetro’s mother’s die in a car accident. Right before the ballet, we see Tetro’s eyes in extreme close-up staring straight into blinding light, which flares off the glacier landscape of Patagonia. Cut to the ballet scene: a duet to repre- sent Tetro and his mother. The blanched Patagonia landscape turns into an artificially (recalling early cinema yet digitally constructed) night scene. The light bursting off the glaciers turn into two headlights of an unseen car, with the dancers rolling out onto a line of blood on the road. This 1 1⁄2 minute scene, set to music of female voice and a heart beat, in the spectral landscape, shot from extreme high and low angles, could be a miniature ballet film gem in and of itself.

The scene becomes Tetro’s trance-like staring into the haunted darkness and blinding light within himself. His mind transforms the reality of death into a scene of transcendence, like a sacred rite, with the mother coming alive as a red-robed spirit wafting up into the black air, as Tetro is left below on the line of blood, reaching after her. The color red being symbol- ic not only of blood, but of blood ties.

All the dance scenes not only metaphorically image the past, but also presage what we don’t know about that past that finally is revealed at the end of the film. Coppola shows how film dance in a narrative film can operate on a level Jung wrote about – that key visions and dreams contain the power to transform consciousness in a person’s struggle to renew his/her health and life.

Amy Greenfield has made almost forty dance films, videotapes, holograms, multi-media performances and installations. Her work has been shown at such festivals as the Berlin, London, Edinburgh, New York, Houston, in one woman and group shows at the Museum of Modern Art, The National Gallery Of Art, and The Whitney Museum.